Two Co Armagh mothers who both lost their sons to suicide are campaigning for improved support services for post-18 autistic people with mental health difficulties.

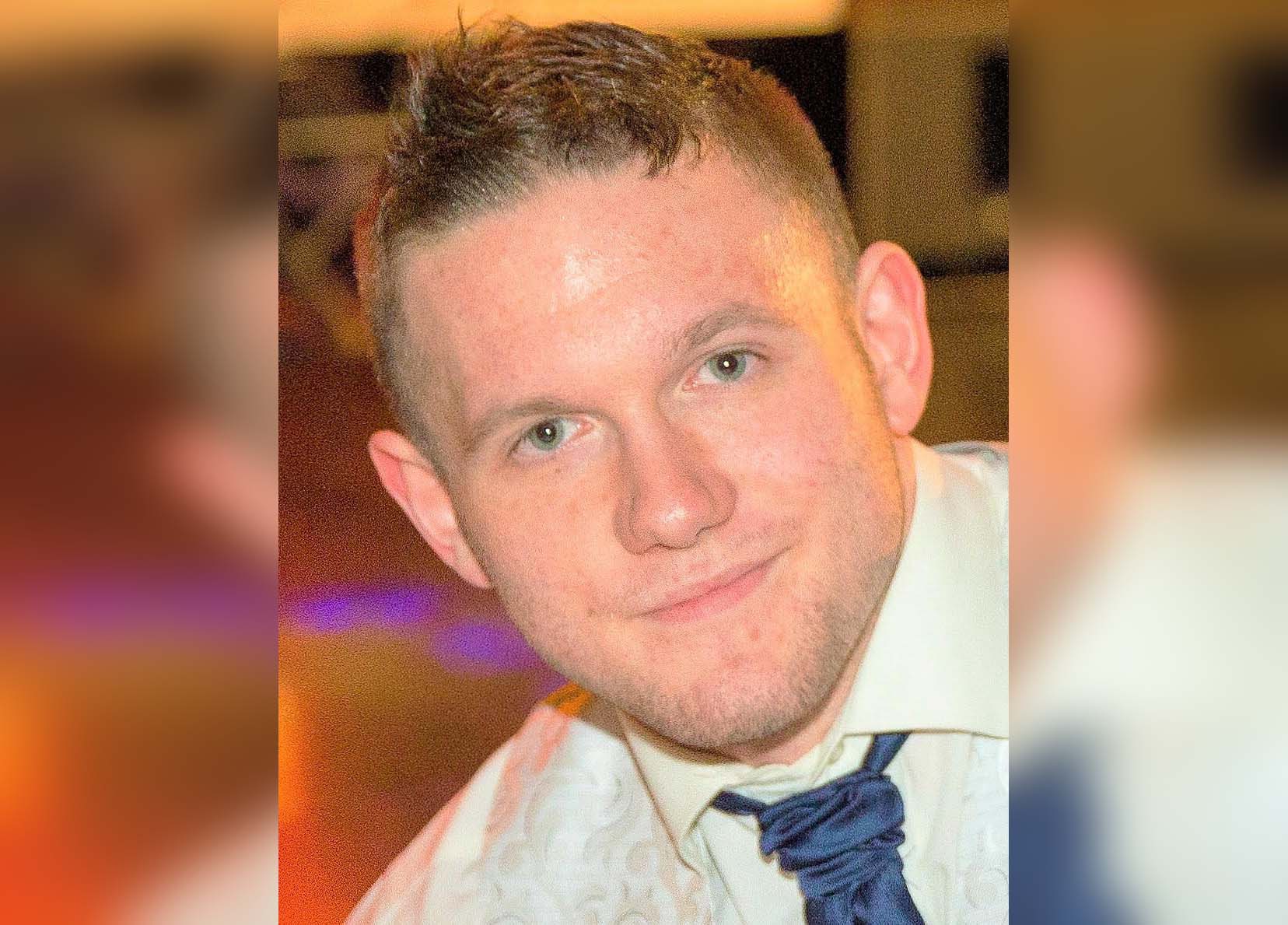

Deirdre Duffy, from Armagh, tragically lost her son, Conor, on April 1, 2014, whilst Julia McKeever lost her son Luke in February of this year.

In Julia, Deirdre told Armagh I she found a “life long friend” when she reached out after reading her story on our website.

The pair found a common goal in trying to ensure that better services, support and strategies are available to those in the situation they had been.

Deirdre said: “It is too late for our sons but there needs to be better resources and support in place. I don’t want Conor to have just died and disappeared whilst so many are suffering in the same way he did.”

Deirdre and Julia have already made great strides and are set to meet the Health Minister Robin Swann to discuss the issue.

Sharing her story, Deidre began by recalling her son’s early years and her struggles to have him diagnosed.

“Going back to his really early years, as an infant, his milestones were all delayed and we just knew that something was not right, that there was something ‘different’, shall we say, about him,” she said.

“I already had a daughter, who was three and a half years older than Conor, but even as a mother I just knew he was not developing in the average way.”

He was referred to the child development clinic, at Craigavon Area Hospital, where he was seen by neurologists, psychologists, psychiatrists and paediatricians but there was still no diagnosis.

However, when Conor was eight his mother Deirdre, who has a background in special needs teaching, attended a National Association for Special Educational Needs conference in Belfast.

She recalled: “There were a few options of lectures to attend, so I chose to go to one about autism and Autistic Spectrum Disorders, just out of interest.

“Autism was not really a thing back when Conor was a baby, but I can remember listening to that lady thinking that he ticked every box. She may as well have been referring to Conor.”

Following this, Deirdre attended the GP to get her son a referral but they were unsure of where this should be made to and sent them to a Child and Family clinic in Dungannon.

“After weeks of questions, we were given a report that stated Conor didn’t fall into the category of autism and didn’t present with any mental health difficulties, but we knew that he did because he was full blown at home,” she explained.

“We ended up paying privately for a diagnosis when Conor was 11, but that private diagnosis didn’t really hold any weight in the educational system or with the medical people.”

Deirdre recalls the family feeling like they were “left to their own devices” with no support or strategies in place to help them as Conor developed into his teenage years and displayed increasingly challenging behaviour.

“He would go into fits of rage, but it was really frustration,” she explained. “He knew he was different but he didn’t like it. We told him he had the diagnosis but he just did not want to know anything about it.

“He really struggled, because not only was he different but he wasn’t on par with his peer group either.”

Without a statement of educational needs, Conor remained in the mainstream school system and received a classroom assistant but Deirdre championed the work of his teachers.

Deirdre said: “They were all great. They were actually able to, between myself and my husband through email, let us know where his deficits were.

“My husband would help him out on the maths side, as he works as an engineer, and then I was able to help him with the literacy subjects.”

Through all of this hard work, Conor was able to leave school with a total of five GCSEs.

The school had promoted his keen interest in computing and he would go on to complete a BTEC at the Southern Regional College in Print Media.

At the age of 17, Conor developed another interest in the gym which he regularly attended.

“He built up muscle, he made friends at the gym, not really close friends, but he was sociable there and he felt comfortable there, it was his happy place,” explained Deirdre.

“I think he was like any other 17, 18, 19-year-old. I think Conor would have liked a girlfriend and I think that was probably one of the reasons he wanted to build muscle.”

However, as time went, when not at the gym Conor became more and more isolated, locking himself in his room playing computer games.

“His mental health was suffering, there’s no doubt about that but there was no support, no help, no strategies and we didn’t know if what we were doing was right or wrong.”

This all came to a head as the family learned the full extent of Conor’s problems around Christmas of 2013.

“On Boxing night, he locked himself in his bedroom and we couldn’t get access to him,” Deirdre recalled. “He seemed very scared, he had some alcohol taken, not a lot, but he wasn’t a drinker, and we thought it had maybe taken hold of him.

“He wouldn’t open the door, he was screaming and shouting for us to get away from the door, that there was some type of danger. It was a full blown psychotic episode but we didn’t know what it was called at the time.”

Conor became distressed again on New Year’s Eve, with his mother describing how she nursed him crying through into the next morning.

This was a wake-up call for the family. The next week Conor was persuaded by his sister to go to the GP and was prescribed anti-depressants.

Following this, Deirdre can recall a sense of hope and happiness as Conor moved into his own home at the Sheils Houses in Armagh and her daughter got married on March 14.

She said: “It was one of the great weddings, then my daughter and her husband went off on a two week honeymoon and the weekend they came back me and my husband went to our holiday home.

“We came back on the Monday evening. I went to work the next day and my husband had been trying to contact Conor about getting his washing machine sorted in his new house all day but there was no answer.”

Later that day, Deirdre, her husband and her daughter attended Conor’s home.

She describes walking in behind her husband and being told by him not to walk any further, as Conor had sadly taken his own life.

Just three weeks after celebrating their daughter’s marriage, Deirdre and her husband were now burying their 20-year-old son.

“We were all very ill, we didn’t know who to turn to and we were suffering with panic attacks but we didn’t know that and kept thinking we were having heart attacks because of the trauma of it all,” she said.

“Then my husband was searching online and found the Niamh Louise Foundation. They were just absolutely amazing and supported us so much. They were a great help as some of them had gone through the same experiences.”

Seven years on and Deirdre says that the family still benefit from the help of the foundation, attending weekly coffee mornings.

“Even after all this time, it is still very raw and Conor is still very much a lift to me. I mean I almost expect him to come running down the stairs, his is still a presence in our home and everywhere we go.”

Then just four months ago, during a late night scroll to catch up with the news through Armagh I, Deirdre spotted an article in which Julia McKeever described the passing of her son, Luke, and was struck by the parallels.

“I messaged Julia that night. I was just crying because I could feel her pain. She had only a few weeks previously lost her son who was autistic to suicide.”

The two mothers then remained in contact exchanging information about their experiences and both decided to work together to make changes.

“We both knew that we needed to do something. It was too late for our sons but there needed to be better resources and support in place.

“I am taking to parents now, with autistic children with mental health issues and they to are also saying the support is not there. We are working to make a change for support for post-18 autistic people with mental health issues.”

Finding kindred spirits, the pair both had a passion for making sure the system is changed and through contact with local government have set up a meeting with Health Minister Robin Swann on August 18.

Deirdre commented: “I am not sure what will happen but it will raise awareness. I believe me and Julia were meant, destined to meet, and that we will be life-long friends as a result of our mission.”