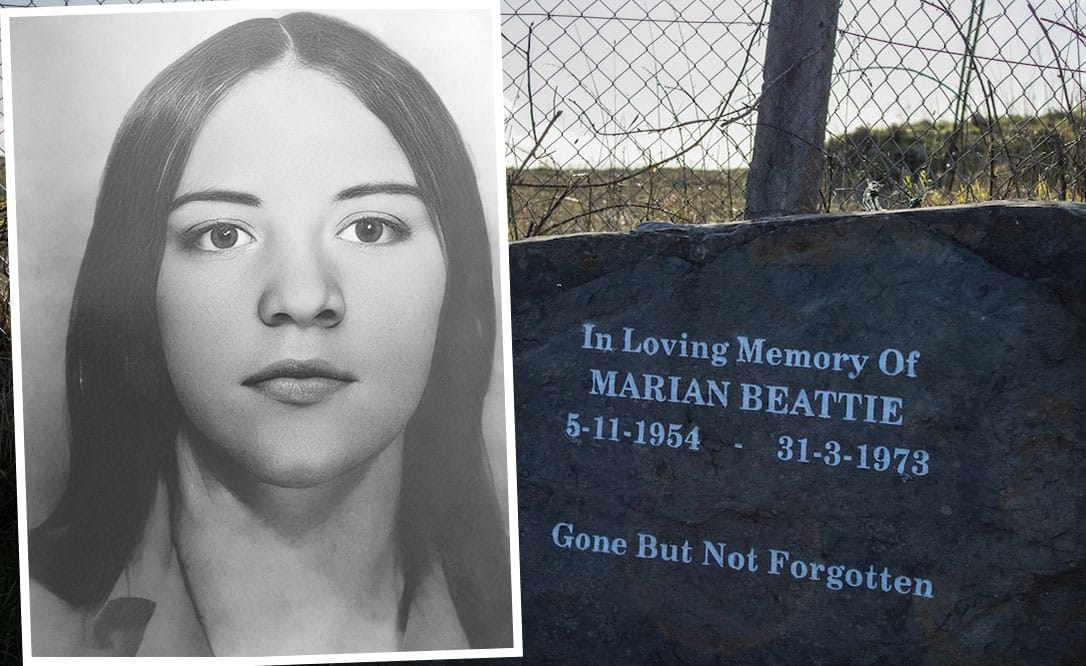

The Police Ombudsman’s Office has recommended that the PSNI should commission an independent review of the murder of 18-year-old Portadown woman Marian Beattie in Co. Tyrone in 1973.

Marian’s partially-clothed body was found at the bottom of a quarry after she had left a dance with an unidentified male in the early hours of March 31, 1973.

No one has ever been charged with or convicted of her murder.

The recommendation for an independent review comes after the Police Ombudsman’s investigation identified numerous failings during police enquiries into the murder.

It found that police had failed to ensure that all lines of enquiry were progressed, that all suspects were interviewed, that all alibis were checked, and that discrepancies between some suspects’ accounts and other evidence were examined.

The Police Ombudsman’s Chief Executive, Hugh Hume, said that Marian’s family had not received the service that they deserved from the police.

“In 50-plus years after her murder, up until earlier this year, there were only eight documented contacts between the police and the family. It is understandable that they have lost confidence and trust in the police,” he said.

“Although our enquiries found no evidence of individual police criminality, nor misconduct by any serving officer, the police investigation of Marian’s murder has been undermined by organisational and systemic failings.”

Mr Hume added that although Marian was murdered in 1973, there were lessons to be learned from the case of relevance to current policing.

“At the time of Marian’s murder the police faced significant policing challenges, with hundreds of murders each year being attributed to ‘the Troubles’, and that context was taken into account during our enquiries.

“Nevertheless, we must learn from past errors and omissions, particularly if we are to properly address the problem of violence against women and girls in local society. Northern Ireland has the second-highest levels of femicide in western Europe,” he said.

“Unfortunately, the Police Ombudsman has found a similar lack of investigative rigour and pre-emptive conclusions in some recent PSNI femicide investigations.

“Police Ombudsman investigations are critical to learning lessons, and it is my hope that our recommendation for an independent review will help to ensure that future police enquiries into Marian’s murder are comprehensive and focused.”

The night of the murder

Marian went missing after attending a dance at Hadden’s Garage in Aughnacloy on the evening of 30/31 March 1973.

The event had been attended by around 400-500 people from the local area and beyond. Marian had gone there with a friend and her older brother, and was last seen alive walking in the direction of Hadden’s Quarry with an unidentified male.

After being unable to find her following the event, Marian’s brother reported her missing at Aughnacloy Police Station. Police conducted searches and her body was found at the bottom of the quarry, beneath a 90 foot drop, at around 6am on 31 March 1973.

A post mortem examination undertaken later that day concluded that Marian had died from multiple injuries. Some of these were consistent with a fall to the quarry floor, particularly injuries to the left side of her body.

However, other injuries were deemed to have been sustained separately.

Initial police enquiries

The Police Ombudsman investigation found that the RUC reacted quickly following the discovery of Marian’s body, dispatching Criminal Investigation Department officers and a Scenes of Crime Officer.

Items were recovered, including articles of clothing and forensic samples. These were submitted for analysis to the forensic science laboratory and returned to the police on 18 January 1974.

There is no record of what happened to them after their return to police and all are now missing.

They include a palm print, formed in mud on the heel of Marian’s right shoe, which became a significant focus for police. Although a photograph of the print does still exist, the shoe itself is missing.

Police records indicate that 419 people who had been at the dance were located and interviewed by police, using a standard questionnaire format. Although the questionnaire that was used is still available, all completed questionnaires are amongst the missing documentation.

Over-reliance on palm prints

During the initial police investigation a large number of palm prints were obtained to compare against the palm print formed in mud on Marian’s shoe. No match was found.

However, Mr Hume said that although palm prints formed a central aspect of police enquiries, this was problematic for a number of reasons.

These included the poor quality of the muddy print found on Marian’s shoe. Mr Hume said it was clear from the evidence that enquiries relating to this print “would not be capable of providing a positive identification.”

“This does not necessarily mean that the palm print would be incapable of use for the elimination of suspects; however, the poor quality of this mark suggests that it should not be relied upon as the only reason for elimination.”

“More weight was placed on the value of the palm print to the investigation than it could bear.”

He added that the reliance on palm prints was also based on the assumption that the print on Marian’s shoe had been left by her killer.

“This assumption narrowed the focus of the investigation and may have resulted in missed opportunities and weak decisions. When palm prints were found not to match, police most often failed to conduct any further enquiries.”

It was also found that the examination of palm prints were the only enquiries conducted in relation to three suspects, resulting in their exclusion from the investigation prematurely.

Investigative errors and omissions

The Police Ombudsman’s investigation identified that police investigating Marian’s murder had missed numerous evidential opportunities, including “reasonable lines of enquiry that do not appear to have been followed.”

However, it also found that – due to the passage of time, the loss of records and exhibits, and the fact that investigators were unable to speak to many officers involved in the murder investigation – it was not always possible to establish whether lines of enquiry had been followed and not documented, or whether they had not been progressed at all.

For the same reasons, Police Ombudsman investigators were often unable to determine the rationale for decisions taken during police enquiries.

Nevertheless, Mr Hume said it was clear that there were significant outstanding lines of enquiry in relation to suspects that had not been pursued.

In particular, he said Police Ombudsman investigators had found no evidence that police had:

- conducted any interviews with a number of suspects;

- checked a number of suspect alibis;

- made enquiries about the whereabouts of some suspects on the night of the murder;

- examined discrepancies between the accounts of some suspects and other evidence;

- undertaken any intelligence work in relation to suspects;

- shown a photograph of Marian to witnesses during their initial enquiries, or asked whether they had seen her leaving the dance hall.

Police were also found to have made only limited use of identification procedures in a bid to establish the identity of the male seen leaving the dance with her.

On one occasion police interviewed a suspect in a way that was not in accordance with relevant codes of practice.

The report also notes that the police Serious Crime Review Team recommended in 2011 that all witnesses and police officers involved in the initial police investigation should be traced and interviewed.

However, only a “relatively limited” number of witnesses were interviewed during this process, and interviews with police officers were also incomplete.

Loss of exhibits and investigative records

Although a substantial amount of material was available to Police Ombudsman investigators, their enquiries, as well as those undertaken by police, were significantly hampered by the loss of police exhibits and documentation.

The missing material includes documentary evidence, statements, records of interviews with witness and suspects, and officers’ journals.

All physical exhibits recovered during the initial police investigation are also missing, and Mr Hume said this had had “a serious” impact on police investigations.

“If these exhibits had been available, it may have been possible to have conducted further forensic testing using current forensic capabilities, and it is possible that this may have resulted in the identification of the person responsible for Marian’s murder,” he said.

The Police Ombudsman’s investigation found that at the time of the initial police investigation, there was no central repository for investigative records, nor a property management system for managing exhibits.

“This is a recurring systemic issue that Police Ombudsman investigations of historical matters have established in other cases,” said Mr Hume. “There is anecdotal information that exhibits from historical cases have been located in recent years in police stations, in areas such as in stairwells and loft spaces.”

The Police Ombudsman’s investigation acknowledged, however, that efforts were made by the police Serious Crime Review Team in the mid-2000s to locate the missing exhibits, consisting of searches at Dungannnon, Omagh and Aughnacloy police stations, which were ultimately unsuccessful.

It also noted that there are now systems in place for the management of records and exhibits.

Police communications with Marian’s family

The Police Ombudsman’s investigation found that up until earlier this year, there are only eight documented contacts between police and Marian’s family in the five decades since her murder – although investigators noted that records of the actions taken by police were incomplete.

It was unclear whether the family were informed of any progress or decisions made by the initial police investigation team, including the decision to close that investigation.

No records of any contact with the family were found prior to 1986, when Marian’s brother contacted police to provide them with an anonymous note the family had received about a potential suspect.

The next documented contact with the family was not until 2007.

In 2014, the family were told during a meeting with the police that there were no active lines of enquiry, and that although the case was not closed as it remained an unsolved murder, there would be no further investigation unless new lines of enquiry came to light.

However, Police Ombudsman investigators established that at this time there were over 200 incomplete actions noted in the investigation management system used by the police investigation team.

“I am concerned that the family were led to believe that the investigation was effectively complete, because that does not appear to have been the case,” said Mr Hume.

“Marian’s family have lost confidence in the police. There should have been greater levels of communication and transparency.”

Family members also advised Police Ombudsman investigators that police had made comments on four separate occasions that led them to believe there were potential links between suspects and either police, military/security services or paramilitaries.

Although there were no police records of this being discussed, available information suggests it is more likely than not that such comments had been made.

The Police Ombudsman investigation found that three suspects had paramilitary links and two were former police officers.

In addition, while clear lines of enquiry were outstanding in relation to the suspects known to have potential paramilitary and police connections, this was not unique to these suspects, and the Police Ombudsman investigation was unable to establish whether or not these connections had any impact upon the police investigation.

“Although our investigation has found significant errors and omissions during the police enquiries into Marian’s murder, it is my hope that the independent review we have recommended will ensure that every effort is made to uncover the truth about her murder, and to finally bring her killer, if still alive, to justice,” said Mr Hume.

PSNI response

Deputy Chief Constable Bobby Singleton said: “Marian Beattie was an innocent 18 year old who was murdered while attending a charity dance at Haddens Garage near Aughnacloy on 30 March 1973. Our thoughts are with Marian’s family today and we recognise the suffering they have experienced over the years in their quest to have someone brought to justice for her murder.

“We are committed to helping the Beattie family get answers to their questions and ensure the case is properly investigated.

“We will now take time to consider the recommendations of the Police Ombudsman report and we hope the family will engage with the Police Service as part of that process.”