The Police Ombudsman has concluded that failings in the RUC investigation into the Kingsmills atrocity, including the failure to arrest suspects linked by intelligence to the attack, took place against a backdrop of ‘wholly insufficient’ resources.

In a report published today (April 29), Marie Anderson recognised the ‘intense pressure and strain’ that RUC officers faced in 1976, when investigating one of the worst atrocities of the Troubles when ten men were murdered.

As well as identifying the failure to arrest and interview 11 men identified by intelligence, the Police Ombudsman also found that the original investigation failed to exploit ballistic links with other attacks in which the same weapons were used. There were also missed investigative opportunities and inadequacies in areas such as forensics, fingerprints and palm prints, and witness enquiries.

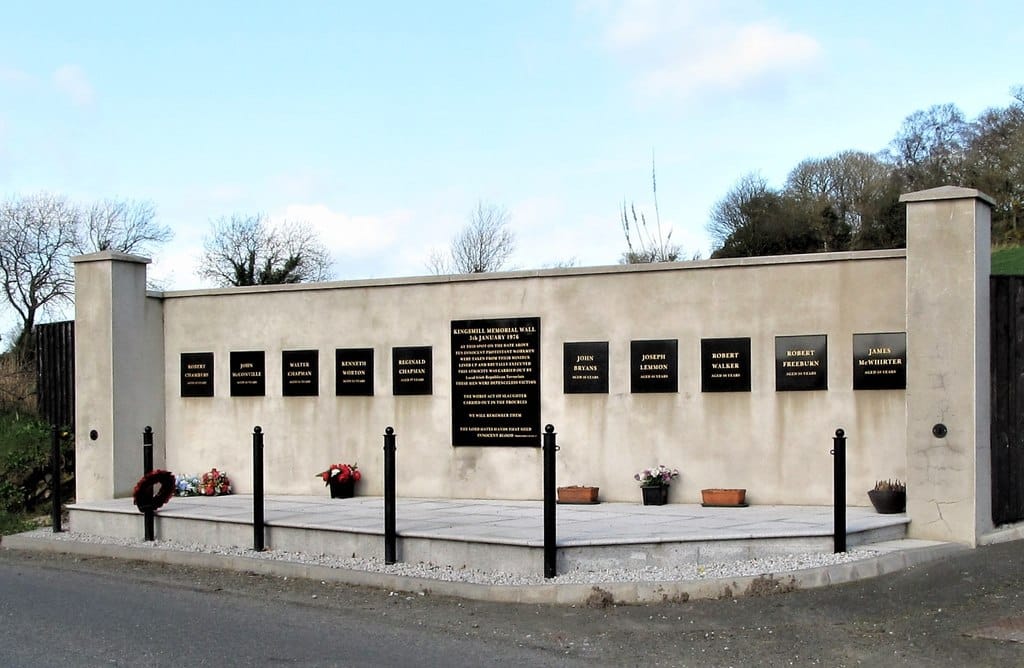

The ten Protestant workers were murdered by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) when the minibus taking them home from work at ‘Glenanne Mill’ was stopped by a group of armed men on the Kingsmills Road, County Armagh, on 5 January 1976.

One passenger, identified as a Catholic, was told to leave and the remaining 11 men were shot multiple times. Only one man, Alan Black, survived.

The murders were said to have been in retaliation for loyalist paramilitary attacks carried out the day before on the Reavey and O’Dowd families which resulted in the deaths of six people.

One of the worst terrorist incidents

In reporting her findings, Mrs Anderson emphasised that police officers who attended the scene immediately after the attack were ‘faced with one of the worst terrorist incidents to occur in the Troubles’ and ‘conducted themselves in a professional manner, identifying witnesses, recovering evidence, and conducting other enquiries in the area.’

She also recognised ‘the intense pressure and strain’ that the RUC and its officers were under in 1976, the second worst year of The Troubles in respect of fatalities:

“By today’s standards, the investigative resources available were wholly insufficient to deal with an enquiry the size of the Kingsmills investigation. The situation was exacerbated by a backdrop of multiple terrorist attacks in the South Armagh and South Down areas that stretched the already limited investigative resources available even further.

“The detective leading the investigation had a team of eight to assist him in investigating ten murders and an attempted murder, which was supplemented for only a matter of weeks by two teams of about eight to ten detectives from the RUC’s Regional Crime Squad. This was entirely inadequate,” said Mrs Anderson.

Investigative failings

Against this backdrop, the Police Ombudsman identified a number of investigative failings, leading her to conclude that complaints in relation to the conduct of the original police investigation were in large part ‘legitimate and justified’.

Suspects and Arrests

Police Ombudsman investigators identified over 60 individuals who were listed in the RUC investigation files as suspects during the police investigation. A number of these were identified in intelligence received by police as active PIRA members.

Of these, nine were arrested by police in January 1976 and another one the following month. An eleventh arrest took place ten years later in August 1986.

All 11 suspects were interviewed by police and subsequently released without charge. None of them spoke during police interviews.

No reason could be established as to why a further arrest, scheduled for mid-January 1976, did not take place. Plans to arrest another two identified suspects were also cancelled and the same applied to a third individual who was to be arrested in mid-January 1977. There is no record that these arrests ever took place, and if not, why decisions were reversed.

Although the RUC arrest strategy, confirmed at the Kingsmills Inquest, was largely centred around intelligence and other information received by the investigation team, Police Ombudsman investigators were unable to find any recorded rationale as to why certain individuals were arrested and other suspects were not.

There were instances where there was no record of enquiries in respect of identified suspects having been progressed. This included an individual stopped at the Kingsmills scene, following the attack, who was ‘thought to have IRA connections’.

In late 1976, the RUC police investigation team obtained information, which identified 11 men responsible for the Kingsmills attack.

Early intelligence implicated one man, Person B, as being one of the gunmen. He was outside the jurisdiction at the time of the investigation and has never been arrested in connection with the Kingsmills attack.

Police had also received information that a man, Person F, suspected of being responsible for hijacking the Bedford minibus used by the gunmen was involved in the attack. He has never been arrested in connection with the Kingsmills attack.

Police documentation also shows that the investigation team had information implicating others in the attack, including Person Q, whose palm print was later connected to the hijacked Bedford minibus used in the murders. He was not arrested until 2016 by PSNI in respect of the Kingsmills attack. A file was sent by PSNI to the Public Prosecution Service, in respect of the hijacking and theft of the vehicle. The PPS directed no prosecution.

In June 1976, Person R was arrested, with others, during the attempted murder of members of the security forces. The group were found to be in possession of a number of firearms, three of which were forensically linked to the Kingsmills attack. In December 1976, he was on remand awaiting trial. Person R has never been arrested in connection with the Kingsmills attack.

The RUC also had general information that Person S was an Officer In Command in an Active Service Unit of PIRA based in the Republic of Ireland. In late December 1976 the RUC murder investigation team received information that Person S was involved in the Kingsmills attack. He is described as having an accent that sounds like an English accent. Mr Alan Black, the sole survivor of Kingsmills, referred to one of the attackers having an English accent. Person S has never been arrested in connection with the Kingsmills attack.

“Although the RUC investigation received reports that were subsequently found to be inaccurate, vague, or misleading, or generic information relating to PIRA using a cover name afterwards to distance itself from the murders, the information relating to Persons B, F, Q, R and S should have been pursued.

“The unexplained failure to exploit the evidential opportunities that may have been offered by the prompt arrest and interview of these individuals undermined the potential development of further lines of enquiry.”

Ballistics

More than 150 ballistic exhibits were recovered from the scene of the murders and the original RUC investigation established that a total of 11 weapons were used by the gunmen.

The weapons were linked to a series of attacks carried out by republican paramilitaries, both before and after Kingsmills, between March 1974 and September 1987 in Counties Armagh and Down.

Ballistic links included 37 murders, 22 attempted murders, 19 other incidents, and 11 finds of discharged cartridge cases across this time period. A large number of individuals were arrested and interviewed by police in connection with these incidents and a number were subsequently charged and convicted of serious criminal offences, including murder, attempted murder, and possession of firearms. These individuals received lengthy prison sentences.

Mrs Anderson said: “My investigators found no record that police sought to incorporate these other attacks into the Kingsmills murder investigation and investigate them as linked incidents. This included interviewing arrested individuals in respect of the linked incidents about the Kingsmills attack.

“While weapons being linked to two or more attacks does not necessarily mean that the same individuals were involved in them, it does provide opportunities to establish stronger links and create investigative opportunities, aimed at gathering evidence to bring those responsible to justice. My investigators found no evidence to suggest that these other attacks were linked and investigated by the Kingsmills murder investigation team.”

Hi-jacked Bedford Minibus

Immediate enquiries were made by the RUC to identify the vehicle used by the gunmen to drive to, and leave, Kingsmills Road.

The RUC investigation team established that a Bedford minibus belonging to H&P Campbell, which was stolen from two of the company’s employees near Dundalk on the afternoon of the Kingsmills murders by two gunmen, was likely to have been involved in the attack.

The minibus was found abandoned near Dundalk the day after the murders and was recovered by AGS, whose ballistics and photography officers attended the scene and recovered nine exhibits from the minibus.

Only five of these samples were subsequently submitted for examination by the RUC. There are no records which show the outcome of the forensics and the samples cannot be traced. There is also no available evidence which provides an explanation as to why only five samples were passed to the RUC.

The Palm Prints

RUC officers examined the minibus for fingerprints when it was moved to Dublin and two palm prints from the same person were lifted from the front passenger door.

The prints were compared against 11 people, including the H&P Campbell employees, with negative results.

However, one of the 11 suspects had been arrested for terrorist offences in the Republic of Ireland by AGS in October 1975. Although AGS held his finger prints and palm prints, the RUC did not have them on file, and a comparison was not, therefore, made at that time.

AGS forwarded his finger prints to the RUC some years later in April 1981, but his palm prints were not forwarded to the PSNI until November 2010 when the PSNI’s Historical Enquiries Team (HET) was undertaking a review of the outstanding evidence in the case. However, a HET fingerprint expert failed to match the palm prints on two occasions.

It would be over 40 years after the murders, in May 2016, before the palm prints from the suspect were matched to those lifted from the minibus and in August that year, he was arrested. He did not answer any questions put to him about the Kingsmills attack other than to say he knew nothing about it. He was later released without charge.

With the exception of this one suspect and the two H&P Campbell employees, the remaining names which were checked against the palm prints did not feature anywhere else in the original RUC investigation. However, the palm prints of other suspects who had been identified during the investigation, were not compared against the palm prints. Police Ombudsman investigators were unable to establish why this was the case.

Mrs Anderson called the failure to ensure all suspects were subject to fingerprint and palm print checks ‘significant’:

She said: “The original investigation did not have anything other than uncorroborated intelligence naming suspects and anything which could have served to convert intelligence into admissible evidence would have been nothing short of a major breakthrough in the investigation of the murders of ten men and the attempted murder of another.

“I believe the original police investigation failed to properly consider the value of the palm print from the minibus which was probably used to facilitate the movement of the killers before and after the Kingsmills attack.”

A broken wing mirror, recovered from the hi-jacked minibus was examined for gunshot discharge residue but none was found. However, there was no evidence that the minibus itself was examined for gunshot residue. Given the number of weapons used in the murders, the vehicle used to leave the scene would have been heavily contaminated with residue. Its presence or absence would have provided evidence that the minibus was used by the gunmen.

Investigators also found no evidence that the glass from the mirror was compared with glass recovered from the Kingsmills Road scene. Nor were the tyres from the stolen minibus examined for soil and plant samples which may have matched the samples taken from Kingsmills Road.

Another stolen van, found burnt out 13 miles from the Kingsmills scene, was not forensically examined by police. The Inquest was told by a police officer that the van had been stolen after the Kingsmills attack. However, a Special Branch document recorded that the van had been stolen on 4 January 1976, the day before the murders on the Kingsmills Road.

Other Forensics

Although the police were hampered by torrential rain on the night of the murders, the scene was adequately secured and supervised, and allowed for a full forensic examination and the recovery of forensic exhibits.

Among the exhibits were broken glass recovered from the road and soil samples. Both were submitted for forensic examination. However, there are no records that any forensic examinations took place and the exhibits are no longer in existence.

The Threat Call: 31 December 1975

In a phone call to the Glenanne Mill on 31 December 1975, two workers received a threatening message. Police were notified, attended the mill, interviewed the relevant members of staff and informed local RUC stations.

Information about the threat was not shared with the workforce more generally. This issue was addressed by the Coroner during the Kingsmills Inquest, who stated it was unsurprising that the specific information relating to an individual remained private, given that to circulate the information more widely could identify that person as a potential target for a terrorist attack.

However, the threats were not factored into the Kingsmills murder investigation, which both the Coroner and the Police Ombudsman believed represented a missed opportunity.

Mrs Anderson said: “I am satisfied that police treated the threat call appropriately at the time by informing the two employees and not widening concern by informing the remainder of the mill’s workforce.

“However, the timing of the call was concerning and I believe, as did the Coroner, that the threatening call was worthy of further investigation by police after the Kingsmills attack.”

Witness Enquiries

The Police Ombudsman investigation also identified gaps in witness enquiries by the RUC investigation at the time.

The Kingsmills attack required both knowledge of the minibus route and the workers who travelled home on it.

Although police logs recorded the importance of identifying those who typically used the minibus, but who were absent from work on the day of the attack, the police investigation did not thoroughly explore the reasons.

Police recorded a witness statement from one man, who provided a valid explanation for not being on the minibus. Although the RUC investigation papers provided information about why two other men were not on the minibus, Police Ombudsman investigators could find no witness statements. Notably, one man who was also absent, was named in December 1976 by an IRA source as being responsible for the attack. He was never arrested or interviewed, and his absence was not sufficiently examined.

Five workers had already been dropped off by the minibus before the murders. Although police interviewed and took statements from three, there is no record of interviews or statements from the remaining two.

A key witness, the female driver of a red mini, who was flagged down by the worker who had been told to leave the scene by the gunmen and who took him home and then to the police station to report the attack, was never traced by police and interviewed.

There was no record that police traced and interviewed the two drivers of minibuses belonging to a company from the Tandragee area, one of which had been stopped shortly before the attack on the Kingsmills Road but then allowed to proceed. HET subsequently interviewed one of the drivers, who informed them that he was never spoken to by police at the time.

HET was also able to trace and interview another named witness who had been driving along the Kingsmills Road around the time of the attack and was believed to have been diverted by men using a red light.

A woman, who was at the scene following the attack, and whose home was within the parameters of the house-to-house enquiries, was also not visited or interviewed by police.

Vehicle check points set up in the vicinity of the murder scene in an attempt to identify witnesses took place the day after the murders. However, further check points scheduled to take place were cancelled due a lack of resources to provide security cover.

Similarly, while house-to-house enquiries took place on 7 January, those scheduled to be carried out the following day were postponed and Police Ombudsman investigators could find no record that they were subsequently completed.

Missing Records

The Police Ombudsman investigation recovered and reviewed the original archived murder investigation papers, which included investigative actions, a serious incident log, statements, forensic reports and other investigative material. This established that the original police investigation team carried out approximately 73 investigative actions and obtained 51 witness statements.

Police Ombudsman investigators were unable to locate a full copy of the serious incident log which provides a contemporaneous record of the police investigation, including key lines of enquiry initiated and decisions taken by senior police officers.

Records relating to a number of police interviews, policy decisions, the identification and management of scenes, were not found, and nor were the notebooks and journals for the police officers involved in the Kingsmills murder investigation.

“I have commented previously on the absence of relevant documentation and how missing records impede my ability to capture a full picture of RUC murder investigations. I have found this to be a systemic issue.”

Family Liaison

Several family members of those who were killed noted the absence of communication by the police with those who were bereaved.

The attack occurred before the police had dedicated Family Liaison Officers to liaise with the victims’ families. This role was not introduced until 2000 and therefore, no family liaison logs exist. The Police Ombudsman noted the absence of communication that led to further distress for relatives, who were keen to obtain as much information as possible about the police investigation. However, this is a systemic issue that the Police Ombudsman has identified in other similar cases.

Pre-incident intelligence

The Police Ombudsman investigation found no intelligence that could have forewarned of the Kingsmills attack or allowed police to prevent it and did not identify any intelligence that indicated a direct threat to any of the deceased or injured.

Post-incident intelligence

Almost immediately following the murders, police began to receive intelligence and other anonymous information. This included reports that were subsequently found to be inaccurate, vague, or misleading, generic information.

However, other more specific intelligence identified named individuals and their roles in the attack, and indicated that the attack had been planned some weeks before it took place, contradicting the widely held view that it had been a spontaneous response to the Reavey and O’Dowd murders on 5 January 1976.

Some of this intelligence and other information was acted upon by the RUC investigation team, on other occasions it was not. This included instances where identified individuals, named within intelligence as being linked to the attack, were not categorised as suspects and no action was taken in respect of them.

“My investigation has not seen any evidence that was available to the investigation team which would have led to the conviction of any person for the offences of murder and attempted murder.

“I also note the comment made by the Coroner when he said that ‘none of the intelligence material gathered by police concerning individual culpability was capable of being converted into evidence that could have been presented in front of a court. Repetition of intelligence, no matter how often, does not elevate it to evidence’”.

Collusion

Some of the families complained of collusion. The Police Ombudsman said:

“I have taken into account the limitations on my powers to decide on a complaint of ‘collusion’ as outlined in the Court of Appeal judgment in Re Hawthorne and White. In consequence of the judgment of Scoffield J on 6 February 2025, I am unable to form an evaluative view of my own on conduct constituting ‘collusion’ or ‘collusive behaviours’”.

The Military

The Police Ombudsman has no remit to investigate the conduct of military personnel. However, such was the security situation in Northern Ireland at the time of the Kingsmills murders, that police and military personnel often worked closely together, and the actions of military personnel featured in aspects of the investigation.

Having reviewed all of the relevant information, the Police Ombudsman concluded that military personnel were not intentionally kept away from, or instructed to avoid, the area of the attack on the evening of 6 January 1976. There was also no evidence that any covert police or military operations were ongoing at the time.